Yes, this is really Windows 3.1 — and it’s all due to Delphi.

In 1995, I was twelve years old. I’d loved programming since I first encountered a computer: when I was much younger, about four, my parents bought a BBC microcomputer. Apparently I loved it so much they were concerned and hid it away until I was about eight or nine, and after programming with that for a couple of years I got a series of secondhand PCs, 386es and 486es, on which I installed DOS, Windows 3.1, Windows NT 4 eventually, and more. On the DOS machines I used Turbo Pascal, and then one day my father came home with a copy of Delphi.

Until then, my programming had been for fun, and mostly to customise my computer. I’d write DOS programs that changed the console colour, or experimented with graphics, or make a game, or a password entry on boot. At twelve, I hadn’t really understood what was possible in terms of creating ‘real’ applications. Programming was playing.

Something different happened with Delphi. And that something was called Calmira.

Real Software

All through life, but especially as a teenager or young adult, you have moments where you find can you conceptualise something you could not before. We use phrases like ‘it just clicked’ to describe this, but I’m not describing a moment where you just understand something you didn’t before, but a deeper change in your thought model. They are situations where you lack some key knowledge or insight or ability to conceptualise that prevents you understanding and visualising a concrete idea, and at some moment, this changes and not only do you understand something you did not before, but you also become more capable of abstract and conceptual thought in areas you were not. I remember the first time I ‘understood’ object-oriented programming (before, I had written largely procedural programs passing structures/records): this was not just understanding it, but with that step opened up a vista of other concepts I now had the ability or the mental toolkit to understand. Something had changed in my ability to create mental models. I also remember how, and older than a teenager, I could not understand how to move overseas (I had—and could not get, no matter how I imagined—no picture of how it worked, what daily life would be. How did you find apartments in, say, France? What happens when you step off the plane and try to begin a new life, that first 24 hours? I couldn’t picture it. I solved this by simply doing it, and through doing, understood.) There have been several moments like this, of difficulty grokking followed by a change in mental models, in my, and probably your, life.

At twelve or thirteen, I had a similar problem with software: I was playing. I had not yet realised, and did not really understand the possibility, that I could cross the gap to writing ‘real’ software: software that performed an essential function, or looked and behaved like part of the operating system.

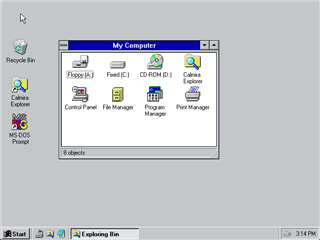

Windows 95 had just come out. I had neither a computer powerful enough to run it nor a copy of it, though desperately wanted both. I enjoyed customizing my computer, and shortly after installing Delphi I came across a replacement shell for Windows 3.1.

It was called Calmira, it made Windows 3.1 look rather like Windows 95, and it was written in Delphi.

Calmira being installed and run. You can download this still today: I recorded this yesterday.

Understanding

Calmira was written in Delphi. It had surprisingly little source code: a few forms, some custom components. The code, while mostly uncommented, was very clean and easy to understand, and I learned a lot about code structure and also writing concisely from it. The key thing though was that it replaced an entire key component of Windows – the shell, the way you interacted with the entire operating system, plus the File Manager, Task Manager, and more – and looked at least to my young eyes remarkably like the shiny, impressive, powerful and new Windows 95. I wanted to understand how it did it.

Here I saw for the first time significant source code not written by me; I saw custom components used in practice; I saw dropping below the wrapper layer that was the VCL to interact with the Windows API and took my first steps understanding what things like handles and device contexts were; I saw simply how something modern (Win 95’s UI) could be easily created – that there was no magic. Shortly after, I started writing my own shell, cloning the Calmira or Windows 95 taskbar and Start menu, and although it was probably terrible code, I succeeded. I often started up and used Windows with my own shell.

But most of all this was a conceptual leap: I moved to thinking, of any app, ‘Software like this can be written — and I can do that.’ I rapidly moved on to writing 3D engines, renderers, chat clients, and only a few years later by University had moved on to C, parsers and evaluators, and a kernel driver (but with a usermode control app in Delphi), and it was all up from there.

The inflection point, the insight, that moment that caused a change in conceptualisation — that was due to Delphi.